The Curious Case of the Uncurious Writer

On Creative Writing Courses, Otherness, and Casual Racism

Disclaimer: The names of persons and companies mentioned in this essay have been altered for obvious reasons.

Sometimes, things happen to me that leave me wondering how to address them. Should this be a short story in which I explore the experience as a motif, an image –turning it into something more oblique, ensuring that people can read it as I intended but also as something completely unrelated? Or should I write an essay and flesh it out? These past two weeks have been… let’s call it eventful, providing me with much inspiration for writing, especially as someone who enjoys dipping her feet into the absurd. This particular thing, though, I feel I must address in an essay – if only to make sense of it myself.

I have written here before about a creative writing course I enrolled in that has a bit of a diversity problem. The course is hosted by a publisher based in London – let’s call them Ashridge. It is taught via Zoom, and though its students are mostly based in the UK, there are couple from Ireland, the US, Australia, and continental Europe. None of this is surprising, nor is it necessarily a problem. What is remarkable, though, is its lack of diversity. I should mention this is my third time enrolling in a course offered by Ashridge. Yet, it is the first time the group is so starkly non-diverse.

As someone who has encountered casual xenophobia while traveling abroad more times than I care to count, I’ve often turned these interactions into inspiration for my short stories. I am no stranger to feeling a bit alien or to being asked questions that would make for excellent sitcom material. During a workshop, this one now up-and-coming writer looked me dead in the face upon learning that I am Brazilian and exclaimed, “Ah, that’s so interesting! There’s a Brazilian cleaner in my next novel!” Some writers from, let’s say, the northern hemisphere, do enjoy portraying us in their workforce. It is a shame these characters are never given even a tenth of the depth their working-class countrymen receive and they will usually be called some unfathomable name. Anyway.

Yes, I am talking about a writing course that is on the pricier side, so it’s hardly surprising that most of my fellow writers fall into a very middle-class demographic. What struck me, though, was just how white the group was. Considering the multicultural, racial, and ethnic makeup of the places my classmates are connecting from - not to mention the fact that Ashridge is based in London, of all places - it felt almost Black Mirror-esque that this group would look so… homogenous. And yet, by the end of the first session, one of them still celebrated how diverse (!) we were.

As the weeks went on, I kept telling myself I needed to chill. This is just your Twitter self talking. No, there’s nothing that grim about the fact that the stories being workshopped are always about melancholy public-school boys or bored middle-aged posh women from Richmond. That doesn’t say anything about… well, anything? And surely, it’s just coincidence that the writers being read as examples - and the ones students bring up themselves - are overwhelmingly white and firmly rooted in the English-speaking world of North America and Europe. It’s fine. Just let. it. go. What on earth did you expect?

But here’s the thing. For someone who grew up and lives in Latin America, it is, at best, baffling, and at worst, mildly infuriating, that you could live somewhere like London or Edinburgh or Dublin and be so thoroughly uncurious about anything beyond yourself. One particular week, there was talk about not making things too confusing for the reader, about providing them with a world they could navigate clearly. I find this problematic in itself in ways that I don’t care to unpack here, but what really struck me was the question of who this imaginary reader was - and why I should be the one to cater to them. If they are so entrenched in their own worldview that they refuse to meet me halfway, why should any of us bother? This reader, I imagine, looks a whole lot like them.

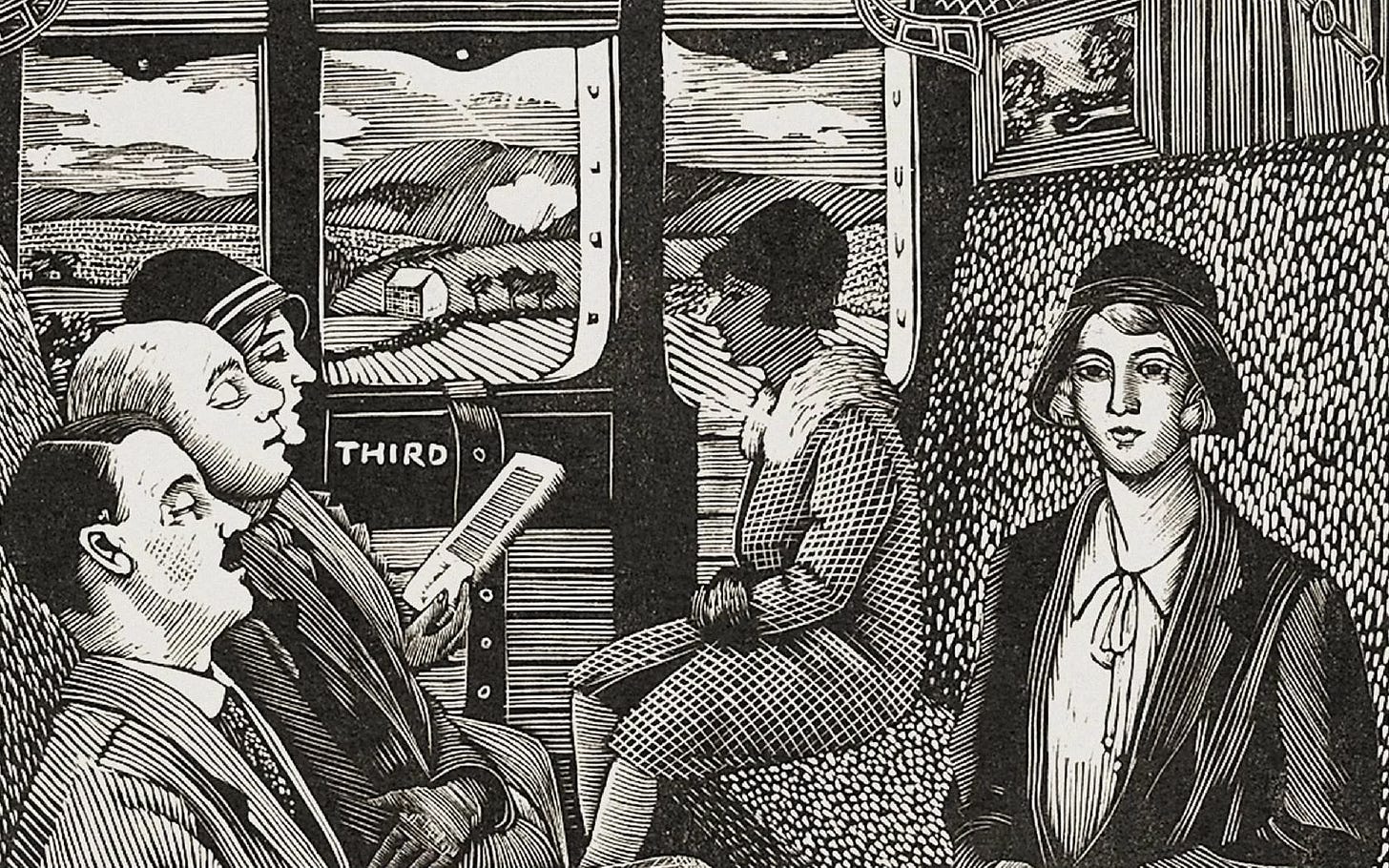

Someone claimed you needed a clear layout: names, descriptions, places the reader could recognise or at least clearly visualise. It made me wonder: if I submitted a story set in Rio - not Ipanema Rio, but Tijuca or Méier Rio - you know, not in the jungle, the mighty jungle - would they even bother to visualise it? If my character wandered aimlessly, not through Charing Cross Road but along Uruguai Street, would they even try to follow? As the weeks went by, these things began to eat away at me. Was I being too harsh? Perhaps.

You may be wondering why I mentioned Latin America earlier. I suppose that we, like other (formerly?) colonised nations and groups in the Global South, have grown up longing for worlds beyond our own realities. This longing is inbuilt in our psyches. We travel abroad - on holiday, on scholarships, through emigration - searching for the parts of ourselves that have been etched into our physical and psychological makeup through osmosis.

I think about Jimmy Kimmel’s surprise when Fernanda Torres mentioned The Mary Tyler Moore Show, unaware that it had aired here. My mum speaks of it with the same tenderness that Fernanda shows in the interview. And yes, I am talking about a kind of cultural imperialism, of course, from Hollywood films to James Bond. But we also care about the world beyond - we grow up on Mexican telenovelas, K-dramas, Turkish soap operas. We are curious about what goes on elsewhere, and we turn these things into memes, inside jokes, pack references to them into own TV and film industries. We are never just one thing or a long list of well-ordered hyphenates. We embrace difference; it is part of our DNA. Not being just one thing, but all things at once - and finding beauty in that.

In Brazil, dozens of book clubs focus on reading fiction from all over the world. We care, we listen, we learn. So the idea of being in London - a place that amalgamates so much diversity, beauty, and possibility - and choosing to only ever read Alice Munro, George Saunders, and… I don’t know, John Cheever alongside some Booker longlisters? Truly, truly baffling.

I tried to articulate this within the group in milder terms, but nothing came of it.

At one point, we were asked to define the human condition in a few words. It was just an exercise in a class on realism, which, you know, fair enough. But I tried to raise the point that anything anyone came up with, no matter how profound or philosophical, would still be extremely empty of actual meaning. Our impressions of the world, of real life, of ourselves - of course, they are subjective in a personal sense, but also in a wider, cultural one. But it seemed odd that nobody wanted to address that at all.

I tried to say - briefly - that any answer would be illusory, considering that the very idea of life or the self varies radically depending on cultural, philosophical, and religious backgrounds. I didn’t say that the reason all the answers sounded so similar was that we were an extremely homogeneous group. My point was quickly brushed off with a “Oh, interesting, thank you.” So from then on, I mostly stayed silent. You don’t want to be the awkward, inconvenient guy who doesn’t know when to shut up, do you?

A couple of weeks ago, my turn came to submit a story for the group to workshop. I didn’t send my Tijuca piece. Instead, I wrote something from scratch - inspired by a recent trip but also by that familiar sense of estrangement, of being made Other in places. Writing course not excluded. It was intentionally oblique. In the story, my character, Margot, travels to Billy Liar’s Ambrosia. In the end, there’s enough room to interpret that she is either turning into a moth or simply done with being the model tourist, the model student, the model teacher. Done with trying so hard to please and somehow always falling short. She doesn’t actually do anything bad or controversial at all, it’s more of a psychological liberation. The idea was that you, as a reader, could project whatever you wanted onto her frustration, her transformation - the same way you can project whatever you like onto, say, Woolf’s lighthouse.

The workshop was… interesting. People were gracious in both their compliments and their suggestions. Truly, there was nothing wrong with it - people were kind. The issue was that there was something fundamental they just didn’t get. I was asked to explain: What is actually happening here? And you know what? I’m all for clarity. Feedback is helpful. But then I found myself trying to explain the piece’s point of departure - that it’s not just about the stress of travelling. It’s about the stress of travelling under a very specific set of circumstances - your gender, your age, the passport you carry.

Only a few days later, a story broke about a famous, wealthy Brazilian actor being publicly harassed and humiliated by the crew on an American Airlines flight. Any person who ever went through that kind of harassment would understand. So, of course, I was made to explain. Because not a single person in that room had any frame of reference for this kind of lived experience. And then someone suggested that maybe the story could be a bit angrier. Well. The point is that if we ever actually are angry when these things happen, we are immediately seen to be in the wrong. We cannot afford to be angry.

But by then, I was tired of explaining. It was a 2,000-word short story. Not much room for exposition. But even if there was, I would never write about this subject matter with anything other than the highest level of ambiguity. That’s the style I strive for. Pinteresque confusion. I was still slightly unsettled by the whole experience when, a few days later, the group was sent the next two stories up for workshop.

I started reading the first. Well. Isn’t it impressive how shitty situations can always get shittier in ways you’d never predict?

On the day I was asked to explain what my story was actually about, I ended up feeling deeply uncomfortable, as if I had been put in the position of spelling out otherness. It seemed an inverted kind of serendipity that the following week, I was faced with not one but two stories that made me long for the days of sad private school boys. For obvious reasons, I’ll describe them only in the most general terms.

The first was written by a gentleman, let’s call him Warren. It focused on a very specific subject: the character undergoes a medical procedure. Warren explained that the story is part of a wider series using comedy to raise awareness about this condition, which is prevalent in his country. So far, so good.

An Ethiopian character appears; her sole purpose? To be praised for her execution of the main character’s Scots accent. Oh, okay? She vanishes.

And then - because apparently, that wasn’t enough - Warren refers to an Indigenous person as an Indian. Worse still, the reference exists solely as the punchline of a joke about the pronunciation of the word shite. Better yet? This is an “Amazonian” Indian. Doing what, you ask? Blowing a dart through a blowpipe. As one does. So I guess we are officially in the jungle, the mighty jungle territory.

It seemed impossible that someone writing in 2025 could be so thoroughly unaware of how harmful this cartoonish 1960s nightmare is, especially considering he claimed to have written this with a radio play in mind (!). I got through it, baffled. Then I read it again, which made it somehow worse.

I moved on to the second story. And then - I can only describe what I felt as the early 2000s experience of hearing Ashton Kutcher yell, “YOU’VE BEEN PUNKED! Because sure, in a group like the one I described, the odds of encountering casual racism at least once are probably reasonable. But twice, in the same week? Yes, reader, please sit down as I inform you that this story uses the word Oriental to refer to a human being. You might be thinking: well, maybe this is about a racist character. Like, say, Marianne’s boyfriend Jamie, who’s a massive racist in Normal People and gets called out by Connell.

But alas. That is not the case. This writer - let’s call her Caroline - submitted a story about a woman in her late 50s, facing her youngest daughter’s departure for university and the collapse of her marriage. It’s all about her: her suffering, her feelings of inadequacy and loneliness, her struggle to navigate this new chapter in her life. Which honestly, great. No problem whatsoever. However, at the beginning of the story, this woman muses that there are mostly Chinese students at an English university. They are “far from home.”

It would sound just a little off, maybe a bit gratuitous if it had stopped there. But no. From there, we move on to a “Thai massage shop” - where the image of a “young Oriental girl” has been defaced by graphic drawings done by “local kids.” You know what? It would take another essay just to unpack everything wrong with that one sentence. But if you are a human being living on Planet Earth, with an internet connection, access to a movie theatre, or, I don’t know, live in a multicultural country, how could you not know this is just reinforcing harmful racial stereotypes?

And yet, nothing comes of it. Nothing comes of the “Asian waiter” or the “Asian barman” either. They are just there: eating kebabs far from home, serving drinks, working in the massage business. Well, I thought. Is this meant to be a joke?

I understood then that the workshop would be the make-or-break moment for me and this course. I decided I would not say anything during it - only a few people get to comment on each story, and I honestly do not feel that, as the de facto minority representative in the group, it becomes my job to explain to people that they are writing what amounts to insanely unacceptable casual racism into their prose. I hoped, rather than believed, that somebody would bring it up. At the very least, the tutor, I thought - a very famous, very successful writer who has traveled the world - would explain that there is such a thing as being sensitive to others. That calling somebody Oriental has not been acceptable since at least, God, Said? That you do not refer to First Nations and Indigenous peoples as Indians, that you do not just throw in nationalities as the butt of a joke. That somebody would, at the very least, ask what the deal with the many references to “Asians” was all about.

People talked about transitions, people took issue with the description of the daughter - was she really an introvert? - people talked about form, about whether this would work in performance, an actor reading on the radio, the pauses, the set-ups, etcetera, but not one single person made the briefest note or took the slightest issue with the racist/xenophobic stuff. That confirmed something terrible to me: the ill feeling I had been getting was not coming out of nowhere. It had the firmest stake in reality. I wondered whether it simply did not register to the group that these were actual, real-world problems, or if they acknowledged it and just did not think it merited a mention.

Real political progress stopped in 2014.

We’re drifting backwards ever since. Strong men.

War.

Unicorn, by Mike Bartlett (61)

Isn’t it scary just how precisely correct Nick, a character from Mike Bartlett’s new play, actually is? The far right is infiltrating the youth through TikTok, Reddit, Discord, YouTube, and god knows whatever else. It manifests either as aesthetically pleasing trends inducing detachment and carelessness or as hatred, pure and simple. I should not, of course, assume that any writer in a writing workshop would be a progressive, but I think I am right to expect some pushback against the kinds of things that just naturally sprang up. If I do not feel safe talking about any of this - if merely writing an allegory on otherness has made me into the other - I get the clear sense that if I were to say anything, it would become a me against them situation. Now look at her: she doesn’t know when to let things slide.

This really, truly sucks on so many levels. First, this course is being taught by a writer I admire and have admired for years. This is not to say I align with everything she has ever said or proposed in her lessons, but dissent had usually been welcomed, even encouraged. But rather than what happened this past week being something that can be undone or just ignored, it now lingers. I feel very uncomfortable there now and can only imagine just how uncomfortable an Asian writer would have felt. Are we welcome at all? A previous course I took there, with this same author, helped me take myself seriously as a writer, to make room for my creativity again after years of feeling that all my writing should be done with academic productivity in mind. But now I feel stumped, like I have run into a wall of unspoken permissions. Like there’s this very prestigious corner of the literary establishment where you get to be low-key racist, xenophobic, and it will be alright. Warren’s story was considered hilarious. Nobody batted an eye at Caroline’s orientalist streak.

I do not mind feeling a sense of unbelonging or of not exactly fitting in. I feel there’s something to be said for navigating through many places without committing to any clubbish rules. To be in transit rather than settled seems like a smart creative decision. But to feel unwelcome, wholly on the outside, is not a nice position to be in either. Like, the reason they could not understand my character’s crisis was that they were the people in her story. I do worry about this cool-vibes literary establishment that you can seemingly find everywhere - we obviously have variations of it in Brazil as well: it is very paulista, very slim, and also very white, - but that’s a conversation for another time. Maybe it would be best if people who are so thoroughly careless or outright hateful did not borrow the language of diversity, or inclusion, or whatever you want to call it, because I, for one, would not have enrolled if I thought this would be regarded as normal.

Writing this is an attempt to work through this strange, strange experience - like I said, not the first, certainly not the last. I have been feeling a bit philosophical lately, thinking about what makes sense as a life goal on a burning planet. Should I worry at all about the opinions of people who do not care about me in any meaningful way, or should I work towards being as thoroughly myself as I possibly can? Should I keep scalding myself in boiling water until I grow accustomed to being burned, or should I work towards not being subjected to a culture that normalises casual violence?

But then again, I think it is impossible not to return to my initial point: this kind of thing would never happen if only these writers had any curiosity whatsoever for things beyond their immediate vicinity. It is fine to write about what you know, but how can you not care enough about the experiences of others to the point of turning them into a prop or an exotic aside? If we are, in fact, drifting away from the progressive politics of the early 2010s - from body positivity to actual conversations about racism, homophobia, and transphobia - then it might be true that the co-opting of these matters by armchair online discourse and, say, girlboss feminism is an immense part of the problem. How thoroughly can you dilute a social issue to make it palatable without erasing it completely?

From the moment Greta Gerwig awarded the cast of Emilia Perez to the fever dream of 2025’s awards season, so many Mexican and Latin American people have raised their voices to criticise the ways in which this film reinforces harmful stereotypes - only to be dismissed by the cast, director, and fans of those involved as haters or trolls. Is it possible that some believe genuine criticism can only be articulated by a certain kind of critic? One who looks a certain way, or hails from a certain place? It was only when the greater public gained access to the film and, ultimately, when Karla Sofía Gascón’s hate-spilling tweets came to light, that at least part of the establishment - journalistic, cinematic - began to pay attention. But still, the problem was minimised, and by turning Gascón first into a pariah and then a meme, the more insidious issues with and around the film remained wholly unaddressed.

From Audiard’s comments on the Spanish language to Saldaña’s dismissal of criticism while holding firmly onto her Oscar, it seems that it is still perfectly acceptable to say that though this film is set in Mexico and portrays mostly Mexican characters, this is not about Mexicans at all. Well, no shit. At the time when Saldaña could not remember how to say things in English because she was so latina, Latin America was already saying that this was not about us at all. So yeah, congrats on the awards, I guess? Why does everybody’s opinions matter but ours?

So you know, going back to thinking of what matters. We think of ourselves through achievement most of the time - credentials, positions, the first to, the best at, chief this, senior that. Does it matter? King of a pond, a nobody elsewhere. It feels exhausting acknowledging that these kinds of horrible hierarchies - these sad, sad remnants or reconfigurations of Empire - still intrude even on a small writing group. I will keep writing, of course I will, but I will also steer clear of the courses and workshops for a while. If you have ever experienced something like this, I hope this essay has somehow helped you feel a bit less alone. I - and unfortunately, I’m sure many others - have been through the same in some capacity, and still, we will persevere in the things that matter.

I have been thinking a lot about something Nnedi Okorafor said at an event at the Southbank Centre last month. Asked whether she ever feels self-doubt, she responded with a resounding no. With no inherent need for validation, she knows what she sets out to do, and she does it with precision and honesty (and is a brilliant writer for it). So, you know what? Spread your little moth wings and do your own thing on your own terms.

Sensacional o texto! Hoje mesmo eu vi um tuíte de uma pessoa dizendo que o novo single da Lady Gaga alcançou o mundo inteiro e diferentes culturas porque viu um vídeo de uma moça vestida de sari dançando ao som de Abracadabra. Como se fosse difícil outros países não saberem quem é cantora underground Lady Gaga 💀

I love your essays. Always thought provoking. No quick sound bites. It’s lazy writing to reach for stereotypes, and also a result of insularity. Bad art as well as painful. I have had the experience and I think you're absolutely right. Open curiosity is what's needed.